Introductory Concepts: The Foundation of Economic Thinking

Let’s be real — economics can feel like a grown-up choose-your-own-adventure where everyone argues over snacks and who gets the last £1. Stick with this quick, exam-focused guide and in about 15 minutes you’ll see how scarcity, supply and demand, elasticities, and a few awkward market failures explain most of the headlines. This is your Markets in Action cheat-code for Edexcel IAL Unit 1 — actually useful, exam-ready, and messy-phone-free. If you’re new to the IAL route, start with our Edexcel IAL overview for course tips and how Unit 1 fits the wider qualification.

Economics = choices + scarcity. At its heart, economics studies how societies use limited resources (land, labour, capital, entrepreneurship) to satisfy unlimited wants. Since you can’t run controlled lab experiments on whole countries (people would notice), economists build simplified models that show what’s likely to happen if one thing changes and everything else stays constant — ceteris paribus. Say that in an exam and you sound like you know what you’re doing.

Two quick-but-crucial splits:

- Positive vs normative: Positive = “what is” (testable); normative = “what ought to be” (opinion). Mixing them up in an essay will get you marked down. Be crisp: state facts, then offer value judgements in evaluation.

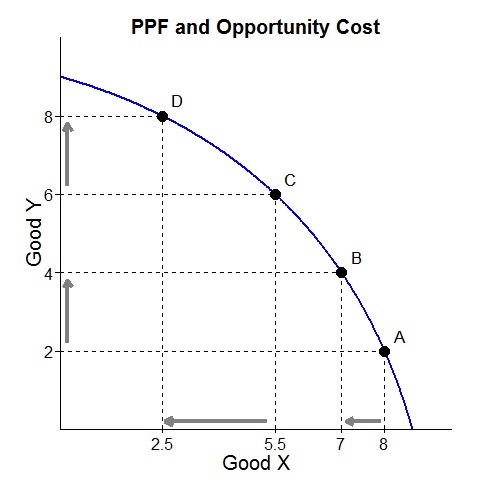

- Opportunity cost: Every choice has a next-best alternative you gave up. Pick Netflix over revision? Your opportunity cost is that lost grade. Mention it.

Concrete example: a pizza shop with ovens that can make 10 pizzas/hour. The PPF (Production Possibility Frontier) for pizzas vs soft drinks bows outward: making more pizzas forces you to give up increasingly more soft drinks because resources are specialised. Training staff or buying another oven shifts the whole PPF out — growth. (If you want a focused walkthrough of scarcity and PPCs, see our CAIE guide on Scarcity, PPCs and Resource Allocation.)

Actionable takeaways:

- Open answers with definitions (scarcity, opportunity cost, ceteris paribus).

- Draw a simple, labelled PPF for trade-off questions.

- Always note models are simplifications — drop ceteris paribus to look professional.

Consumer Behaviour & Demand: Why You Buy What You Buy

Assume rationality — consumers maximise utility given a budget constraint. It’s a simplification, but it works for most exam scenarios.

Demand curve basics: price down → quantity demanded up. Movement along the curve = price change; shift of the demand curve = non-price factor change (income, tastes, prices of related goods, expectations, population). Key elasticities:

- Income elasticity of demand (YED): >0 normal, <0 inferior.

- Cross-price elasticity (XED): >0 substitutes, <0 complements.

- Price elasticity of demand (PED): >1 elastic, <1 inelastic.

Concrete example: student loan day. Demand for sushi (normal/luxury) rises — demand curve shifts right. Instant noodles might be inferior: as income rises, demand falls.

Actionable exam tips:

- For elasticity questions: write the formula, show the calculation, and interpret the number in one sentence.

- State short-run vs long-run — elasticities change with time.

- Use real-life examples (petrol, streaming services) to illustrate elastic vs inelastic.

For a broader run‑through of the specification and exam technique across micro and macro, our Edexcel A‑Level Economics guide is a useful companion.

Supply: What Firms Bring to the Party

Supply = what firms are willing to produce at each price. Higher price → firms supply more (ceteris paribus). Movement along supply = price; shifts = input costs, technology, taxes/subsidies, number of sellers, expectations.

Price Elasticity of Supply (PES): how responsive quantity supplied is to price changes. Short run: capital often fixed → supply inelastic. Long run: firms invest, enter/exit, supply becomes more elastic.

Concrete example: a viral app spikes smartphone demand but factories are locked into schedules — short-run supply inelastic. Over months, production ramps up and supply becomes elastic.

Actionable takeaways:

- Discuss time horizons for PES.

- Draw supply shifts and label old/new equilibrium.

- Note storability: storable goods (wheat) have more elastic supply than perishables (fresh fish).

Price Determination: Where the Magic (and Maths) Happens

Equilibrium: where supply = demand. Shortage → price rises; surplus → price falls. The price mechanism rations, signals, and provides incentives.

Welfare concepts:

- Consumer surplus: willingness to pay minus actual price.

- Producer surplus: actual price minus minimum acceptable price.

- Total surplus: sum of both; markets without distortions maximise total surplus.

Taxes and subsidies create wedges and change surpluses. Example: a specific tax on petrol shifts supply left, raising price paid by consumers and lowering price received by producers. The incidence depends on elasticities — with inelastic demand, consumers bear more of the tax burden.

Actionable takeaways:

- Label diagrams and shade consumer/producer surplus for taxes/subsidies.

- Use elasticities to explain tax incidence.

- Mention deadweight loss when welfare falls.

Market Failure: When Markets Go Off-Script

Markets are brilliant at allocating many resources, but they fail when private incentives diverge from social best outcomes.

Major sources of market failure:

- Externalities: negative (pollution) and positive (vaccination). Private agents ignore third-party effects.

- Public goods: non-rivalrous and non-excludable (street lighting, national defence) — private markets underprovide due to free-riding.

- Imperfect information: asymmetric info leads to adverse selection (used cars) and moral hazard (insured parties take more risk).

- Market power: monopolies restrict output and raise prices, creating deadweight loss.

- Speculation & bubbles: expectations, leverage and herd behaviour can drive prices beyond fundamentals.

Concrete example: vaccines produce positive externalities — vaccinated people reduce disease spread, so private markets underprovide; subsidies or public provision can close the gap [1][5].

Actionable takeaways:

- Draw externality diagrams and mark socially optimal vs private outcomes.

- Link failures to realistic policies (taxes/subsidies/regulation) and evaluate limits (administrative costs, incentives).

- Use current events to make essays concrete — pollution stories, vaccine campaigns, or housing bubbles are fair game.

Government Intervention in Markets: The Toolbox (and the Traps)

When markets fail, governments can intervene. Each tool has trade-offs.

Common instruments:

- Indirect taxes (specific vs ad valorem): discourage harmful goods and internalise external costs.

- Subsidies: encourage goods with positive externalities (education, R&D).

- Price controls: ceilings (rent control) can help short-term but create shortages and lower quality incentives.

- Tradable permits: cap-and-trade creates scarcity in allowances and lets firms buy/sell them for cost-effective pollution cuts (EU ETS is an example) [4].

- Regulation or state provision: direct control when markets clearly fail (e.g., national defence, basic healthcare).

- Property rights & Coase theorem: when transaction costs are low, bargaining can internalise externalities.

Government failure risks:

- Information gaps, perverse incentives, high administrative costs, and regulatory capture.

Concrete example: tradable permits let low-cost abaters sell permits to high-cost firms, achieving emissions cuts efficiently if the cap and enforcement are well-designed [4][3].

Actionable takeaways:

- Always evaluate both market failure and government failure.

- For each policy, say who benefits, who pays, and likely unintended consequences.

- Use evidence (carbon permits, vaccine subsidies) but critique them using practical limits.

Quick Diagrams (Explained in Words) — Draw These Like a Boss

You won’t get full credit for a messy doodle. Describe diagrams clearly if your drawing is shaky.

- PPF: label axes (Good A, Good B). Draw a bowed-out curve. Point on curve = efficient; inside = inefficient; outside = unattainable. Show outward shift for growth.

- Supply & Demand: P vertical, Q horizontal. Downward demand, upward supply. Mark equilibrium (Pe, Qe).

- Tax on sellers: supply shifts left by tax amount (vertical distance). New price to consumers higher; producers receive less. Shade consumer/producer surplus loss, tax revenue rectangle, and deadweight loss triangle.

- Negative externality: private supply = marginal private cost. Social cost is above it. Private equilibrium (Qp) exceeds socially optimal (Qs). Shade external cost.

Actionable takeaways:

- Label everything. Even a messy sketch with clear labels + 1-line explanation scores.

- Practice drawing under time pressure until it’s muscle memory.

FAQs (short, exam-ready answers)

- What’s ceteris paribus? — Hold other factors constant so you isolate the impact of one change.

- How to tell if demand is elastic or inelastic? — Calculate PED (%ΔQ / %ΔP). >1 elastic, <1 inelastic. Example: insulin (inelastic), luxury cruises (elastic).

- Why tax goods with external costs? — To internalise externalities: align private costs with social costs.

- Public vs private good? — Public goods are non-rival, non-excludable; private goods are rival and excludable.

- How does asymmetric information cause market failure? — One side knows more, causing adverse selection and moral hazard.

- When prefer subsidy over regulation? — Subsidies suit encouraging consumption/production with positive externalities and when policing outcomes is hard; weigh costs and risk of overuse.

- What’s deadweight loss? — Lost total surplus when the market is not Pareto-efficient (due to tax, monopoly, externality).

- How do tradable permits work? — Government caps pollution, issues allowances, and permits trading so cost-effective reductions emerge [4].

Closing Kicker

Hot take: master the toolkit — PPF, supply & demand, elasticities, externalities — and you can decode almost any economic headline and answer most Unit 1 exam questions confidently. Practice diagrams, define terms fast, use concise real-world examples, and always evaluate policy with both market and government failure in mind. Want printable, exam-ready diagrams, step-by-step elasticity worked examples, or a timed Unit 1 mock? Say the word and I’ll make them. In the meantime, find printable diagrams and worked examples in our CAIE AS Level Economics Study Notes, and practise under time with our topic questions and timed mocks. For broader exam strategy across specifications, check the Edexcel A‑Level Economics guide.

References

-

Pearson Edexcel International AS/A Level Economics — Unit 1: Markets in Action (specification and student materials).

https://qualifications.pearson.com/en/qualifications/edexcel-international-advanced-levels/economics-2018.html -

Heritage Foundation — 2024 Index of Economic Freedom.

https://www.heritage.org/index/ -

OECD — reports on environment, externalities and public policy.

https://www.oecd.org/ -

European Commission — EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).

https://ec.europa.eu/clima/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets_en -

Investopedia — accessible explanations of elasticity, moral hazard, adverse selection.

https://www.investopedia.com/ -

Britannica — economic history and market bubble overviews.

https://www.britannica.com/