Content

- Topic Questions (MCQ – EASY): Private costs and benefits, externalities and social costs and benefits

- Topic Questions (MCQ – HARD): Private costs and benefits, externalities and social costs and benefits

definition and calculation of social benefits

- Social benefits (SB) refer to the total benefits received by society as a result of an economic activity, including both private benefits (PB) and external benefits (EB).

- Private benefits are the benefits received by the producer or consumer of a good or service

- External benefits are benefits enjoyed by society as a whole that are not reflected in the market price.

- The calculation of social benefits involves adding together private benefits and external benefits. The formula for social benefits can be expressed as follows:

SB = PB + EB

- Marginal social benefits (MSB) refer to the additional benefits received by society as a result of producing or consuming an additional unit of a good or service.

- This includes both the marginal private benefits (MPB) and the marginal external benefits (MEB) associated with the production or consumption of the good or service.

- The formula for marginal social benefits can be expressed as follows:

MSB = MPB + MEB

- Marginal private benefits (MPB) refer to the additional benefits received by the producer or consumer of a good or service as a result of producing or consuming an additional unit of the good or service.

- This includes benefits such as increased satisfaction or revenue.

- This includes benefits such as increased satisfaction or revenue.

- Marginal external benefits (MEB) refer to the additional benefits enjoyed by society as a whole as a result of producing or consuming an additional unit of a good or service.

- This includes benefits such as reduced pollution or improved public health.

- By taking into account both private benefits and external benefits, the calculation of social benefits provides a more complete picture of the total benefits associated with an economic activity, allowing policymakers to make more informed decisions about how to allocate resources and regulate markets.

definition of positive externality and negative externality

- A positive externality occurs when an economic activity generates benefits for individuals or groups outside of the direct transaction, and these benefits are not reflected in the market price.

- For example, a homeowner installing solar panels on their roof generates electricity and reduces their own energy costs, but it also benefits their neighbors by reducing the overall demand for energy and reducing pollution.

- The benefits to the neighbors are a positive externality, as they are not paying for the installation of the solar panels but are still receiving benefits.

- The benefits to the neighbors are a positive externality, as they are not paying for the installation of the solar panels but are still receiving benefits.

- For example, a homeowner installing solar panels on their roof generates electricity and reduces their own energy costs, but it also benefits their neighbors by reducing the overall demand for energy and reducing pollution.

- A negative externality occurs when an economic activity generates costs for individuals or groups outside of the direct transaction, and these costs are not reflected in the market price.

- For example, a factory emitting pollution into the air or water generates costs for nearby residents in the form of health risks and reduced property values.

- The costs to the nearby residents are a negative externality, as they are not benefiting from the production of the factory but are still bearing the costs.

- For example, a factory emitting pollution into the air or water generates costs for nearby residents in the form of health risks and reduced property values.

positive and negative externalities of both consumption and production

- Externalities can arise both from the consumption and production of goods and services.

- Positive externalities occur when the benefits spill over to others outside the market transaction, while negative externalities occur when the costs spill over to others outside the market transaction.

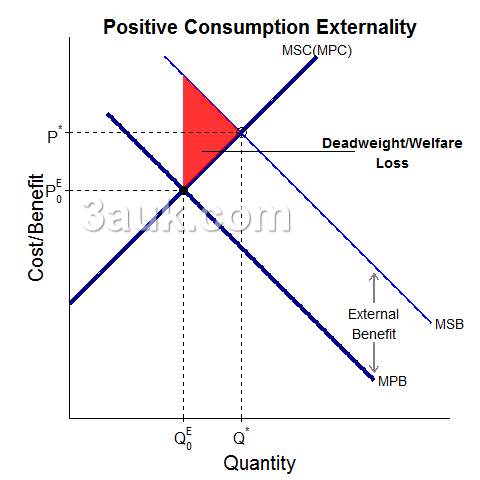

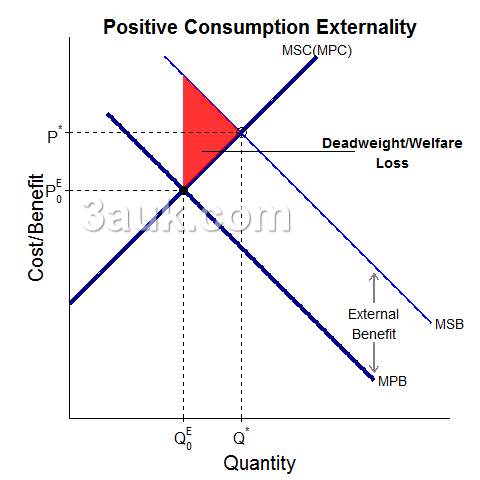

- A positive externality of consumption creates a social benefit that exceeds the private benefit received by the individual.

-

- For example, if an individual gets vaccinated, they receive a private benefit in the form of protection against the disease, but there is also a social benefit in the form of reduced spread of the disease to others.

- If MSB > MPB, there is a positive externality of consumption.

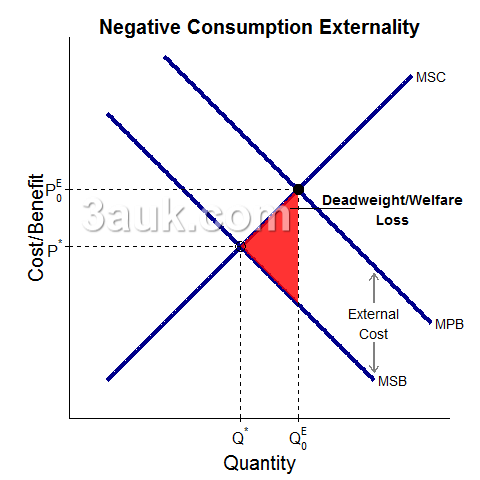

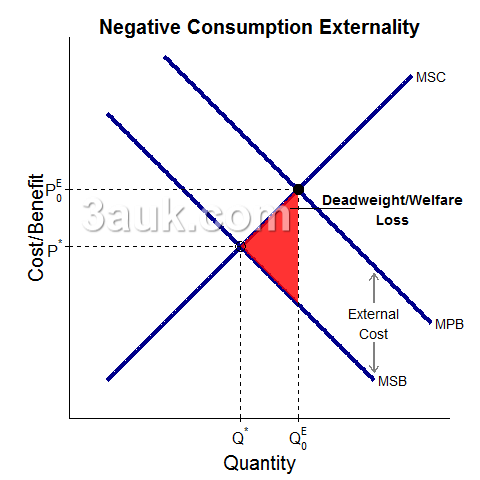

- A negative externality of consumption creates a social benefit that is less than the private benefit borne by the individual.

-

- For example, if an individual drives a car, they receive a private benefit in the form of convenience and mobility, but there is also a social cost in the form of air pollution and congestion.

- If MSB < MPB, there is a negative externality of consumption.

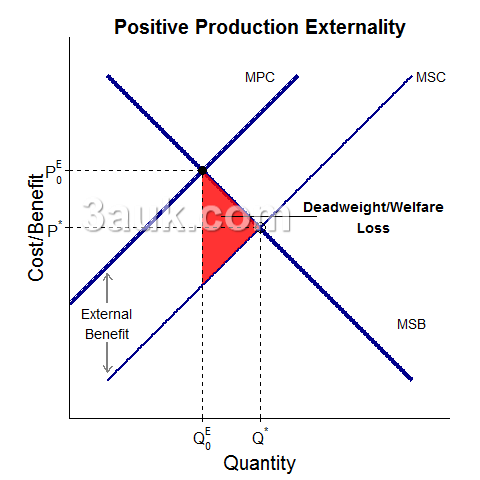

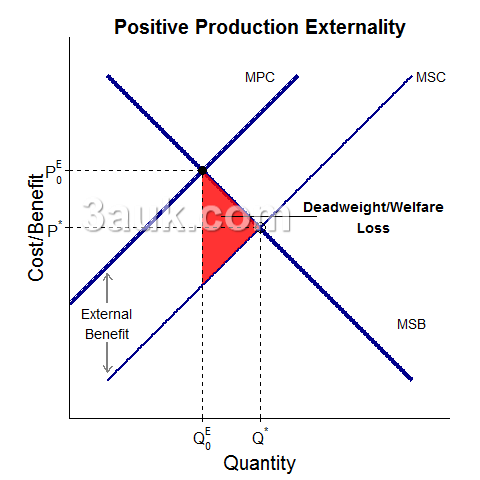

- A positive externality of production creates a social cost that is less than the private cost received by the producer.

-

- For example, if a farmer plants trees on their land, they receive a private benefit in the form of improved soil quality and biodiversity, but there is also a social benefit in the form of carbon sequestration and improved air quality.

- If MSC < MPC, there is a positive externality of production.

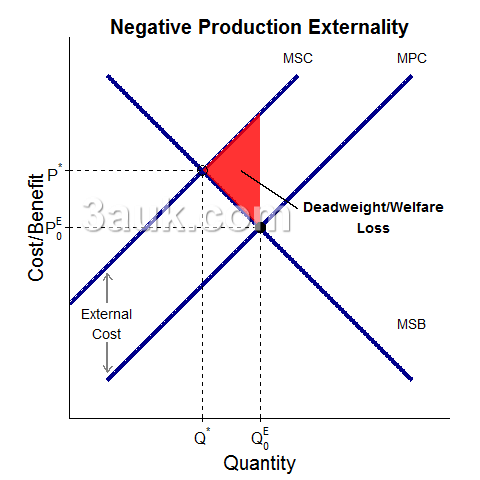

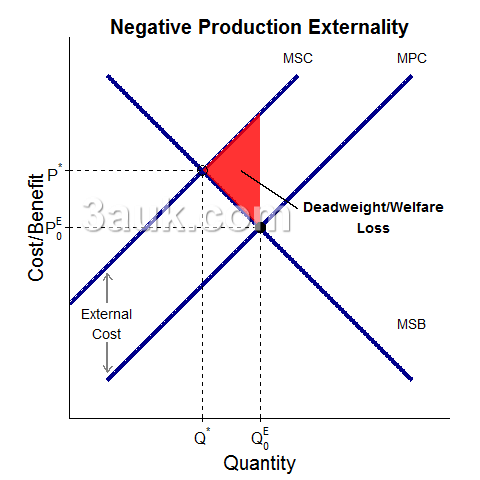

- A negative externality of production creates a social cost that exceeds the private cost borne by the producer.

-

- For example, if a factory emits pollution, they receive a private benefit in the form of profits, but there is also a social cost in the form of health problems and environmental damage.

- If MSC > MPC, there is a negative externality of production.

deadweight welfare losses arising from positive and negative externalities

- Deadweight welfare losses arise from positive and negative externalities when the market fails to achieve allocative efficiency, leading to a loss of economic welfare.

- In the case of a positive externality, there is under-consumption of the good or service as consumers do not take into account the full social benefit.

- This leads to a deadweight welfare loss as the value of the marginal social benefit exceeds the value of the marginal private benefit.

- The market equilibrium results in a lower quantity and higher price than the socially optimal level.

- The deadweight welfare loss is the difference between the social surplus at the optimal level of consumption and the social surplus at the market equilibrium level of consumption.

- In the case of a negative externality, there is over-production and over-consumption of the good or service as producers and consumers do not take into account the full social cost.

- This leads to a deadweight welfare loss as the value of the marginal social cost exceeds the value of the marginal private cost.

- The market equilibrium results in a higher quantity and lower price than the socially optimal level.

- The deadweight welfare loss is the difference between the social surplus at the optimal level of production and consumption and the social surplus at the market equilibrium level of production and consumption.

- Deadweight welfare losses arising from externalities can be significant and have long-term consequences for economic growth and social welfare.

- To reduce deadweight welfare losses, governments can implement policies to internalize externalities, such as taxes or subsidies, to incentivize private agents to consider the full social cost or benefit of their actions. By doing so, markets can become more efficient, leading to higher levels of economic welfare.

asymmetric information and moral hazard

- Asymmetric information refers to a situation where one party has more or better information than the other party in a transaction.

- This can lead to market failure and inefficiencies.

- One example of asymmetric information is the market for used cars. The seller typically has more information about the quality and condition of the car than the buyer. As a result, the buyer may be hesitant to pay a fair price for the car, or may end up purchasing a car of lower quality than expected.

- Moral hazard is a situation where one party is more willing to take risks or engage in potentially harmful behavior because they do not bear the full consequences of their actions.

- One example of moral hazard is insurance.

- If an individual has insurance, they may be more likely to engage in risky behavior, knowing that the insurer will cover the costs of any resulting damages.

- For example, a homeowner with fire insurance may be less likely to install fire alarms or take other precautions to prevent a fire, knowing that their insurance will cover the damages if a fire does occur.

- Another example of moral hazard is the principal-agent problem in business.

- A principal hires an agent to act on their behalf, but the agent may have different incentives or interests than the principal. The principal may not have full information about the actions of the agent and the agent may be more likely to engage in risky behavior or act in their own self-interest, knowing that the principal will bear the consequences.

- For example, a CEO of a company may take risky financial decisions that benefit them personally, but could potentially harm the company and its shareholders.

- One example of moral hazard is insurance.

use of costs and benefits in analysing decisions

- Cost-benefit analysis is a technique used to evaluate the feasibility of a project or policy by comparing its benefits to its costs.

- It involves identifying and quantifying all the costs and benefits associated with a particular decision, and then comparing them to determine if the benefits outweigh the costs.

- The goal of cost-benefit analysis is to make a rational, data-driven decision by weighing the costs and benefits of different options.

- In a cost-benefit analysis, costs refer to all the negative impacts or sacrifices that result from a decision.

- This can include direct costs, such as the cost of materials or labor, as well as indirect costs, such as the opportunity cost of using resources for one project instead of another.

- Benefits refer to all the positive impacts or gains that result from a decision.

- This can include direct benefits, such as increased revenue or improved quality of life, as well as indirect benefits, such as environmental or social benefits.

- This can include direct benefits, such as increased revenue or improved quality of life, as well as indirect benefits, such as environmental or social benefits.

- To perform a cost-benefit analysis,

- Identification of all relevant costs and benefits: This involves identifying all the costs and benefits associated with a particular project or decision. This step involves considering all relevant stakeholders and impacts, including any externalities.

- Putting a monetary value on all relevant costs and benefits: Once all relevant costs and benefits have been identified, the next step is to assign a monetary value to each one. This step can be challenging, as some costs and benefits may be difficult to quantify in monetary terms. However, assigning a monetary value to each cost and benefit is necessary for comparing them and making a decision.

- Forecasting future costs and benefits (where appropriate): Cost-benefit analysis often involves forecasting future costs and benefits. This is particularly important when considering long-term projects or decisions that will have ongoing impacts. Forecasts can be based on historical data, expert opinions, or other relevant information.

- Decision-making: The final stage of cost-benefit analysis involves making a decision based on the results of the analysis. This involves comparing the total costs and benefits of each option and determining which one provides the greatest net benefit. The decision may also take into account other factors, such as risk tolerance, ethical considerations, and stakeholder preferences.

- Identification of all relevant costs and benefits: This involves identifying all the costs and benefits associated with a particular project or decision. This step involves considering all relevant stakeholders and impacts, including any externalities.

- Cost-benefit analysis is commonly used in government and business decision-making, as well as in evaluating public projects and policies.

- However, it is important to note that cost-benefit analysis has limitations, such as the difficulty in assigning a monetary value to intangible benefits or costs and the potential for biases in decision-making. Therefore, it should be used in conjunction with other decision-making tools and approaches.

Join the conversation